What is Listening?

Listen First Project defines listening as an action—the process of lending an ear to another person to take in and organize information, thereby learning from their perspective and formulating more productive communities. Listening is personally attentive and responsive communication that leads to awareness, understanding, and empathy.

1. A genuine desire or motivation to attend fully to the perspectives of others;

2. A range of behaviors that signal attention and interest; and

3. Close attention to and processing of others’ points of view in an effort to understand.

What does Listen First mean?

Listen First to understand rather than to reply

Listen First before rejecting a conversation

Listen First before dismissing alternative ideas

Listen First before launching attacks

Listen First to more effectively advocate your position

Why should I care?

When done well, listening results in a range of positive outcomes including, but not limited to, increased respect, awareness, understanding, and relationship satisfaction.

Learning to listen requires constant practice and re-evaluation. It is an acquired art, not an inherited capacity, and we often fall short; just ask the last person with whom you interacted! Chances are, you did not listen to your fullest. Whether it was a co-worker, client, friend, spouse, or stranger, did you fully attend to their every word? Did you act as if that conversation was the only place you wanted to be? Were you fully present, free from distraction, and engaged to your fullest? Or, did your mind wander? Did your eyes scan the room to see who else was around? Were you tempted to check your cell phone or look at your watch?

“Being heard is so close to being loved

that for the average person,

they are almost indistinguishable.”

How Understanding Others Works

The Listen First Project emphasizes listening to understand – to understand others’ perspectives, feelings, points of view … ultimately, to understand where another is coming from and how best to connect. But how does this process work? Scholars of human communication have studied this phenomenon in depth, and I have tried to summarize much of what we know. After providing a working definition of listening, I then unpack that definition in order to explain how we understand others.

A Basic Model of Listening

Listening is an umbrella term that includes abilities to sense, process, and respond to another individual’s spoken utterances.[1] The three primary building blocks of listening competency (sensing, processing, responding) work in progression. That is, the ability to sense leads to ways of processing that, in turn, determine how one responds. In addition, sensing, processing, and responding are influenced by a range of individual attitudes and predispositions to listen in certain ways. Based on our personality, mood, predispositions, traits, temperament, and a range of socio-cultural and situational factors, we will pick up on certain types of cues from others. These elements also will help determine what types of listening are most appropriate. In other words, how a person listens is a function of both individual characteristics and situational elements.

Now that we have a working definition of listening, let’s unpack it!

Figure 1. A Basic Model of Listening, ©Bodie Consulting

Sensing

When people speak, they do not always say exactly what they mean. Sometimes the meaning of speech is straightforward; other times we have to “read between the lines.” Sensing refers to those abilities to attend to explicit and implicit information generated when another individual is speaking.

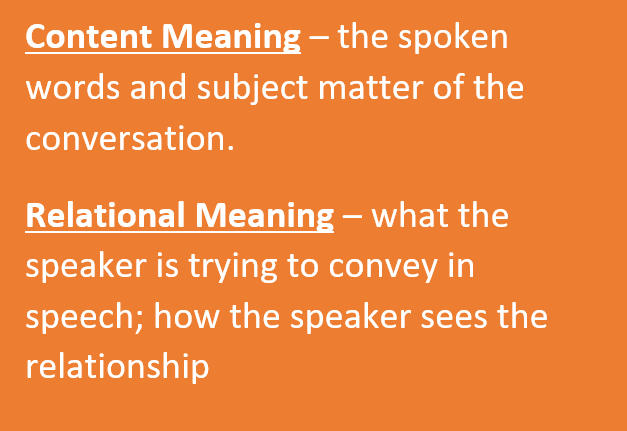

Scholars of human communication have discovered that every message has two broad types of meaning.[2] Content meaning conveys information and is equivalent to the conventional meaning of the message – what can be found in a dictionary, for instance, would be the content meaning of a particular word. So, the content meaning of “dog” is “a member of the Canidae family of the mammalian order Carnivora.”

Relational meaning, on the other hand, is not necessarily found in a dictionary. So, the relational meaning of “dog” could be “man’s best friend” or “a man who treats women poorly” and is entirely dependent on how the word is used in context. More precisely, relational meaning refers to how a message is “to be taken.”[3] In our example, when someone utters “dog” how should you interpret that word?

In general, we interpret others based not only on the words they use but also on how they say those words and on the context in which they use those words. An individual stationed as a lookout while his buddies are breaking into a junkyard yelling “dog” means something completely different than a three-year old saying “dog” while visiting a pet store.

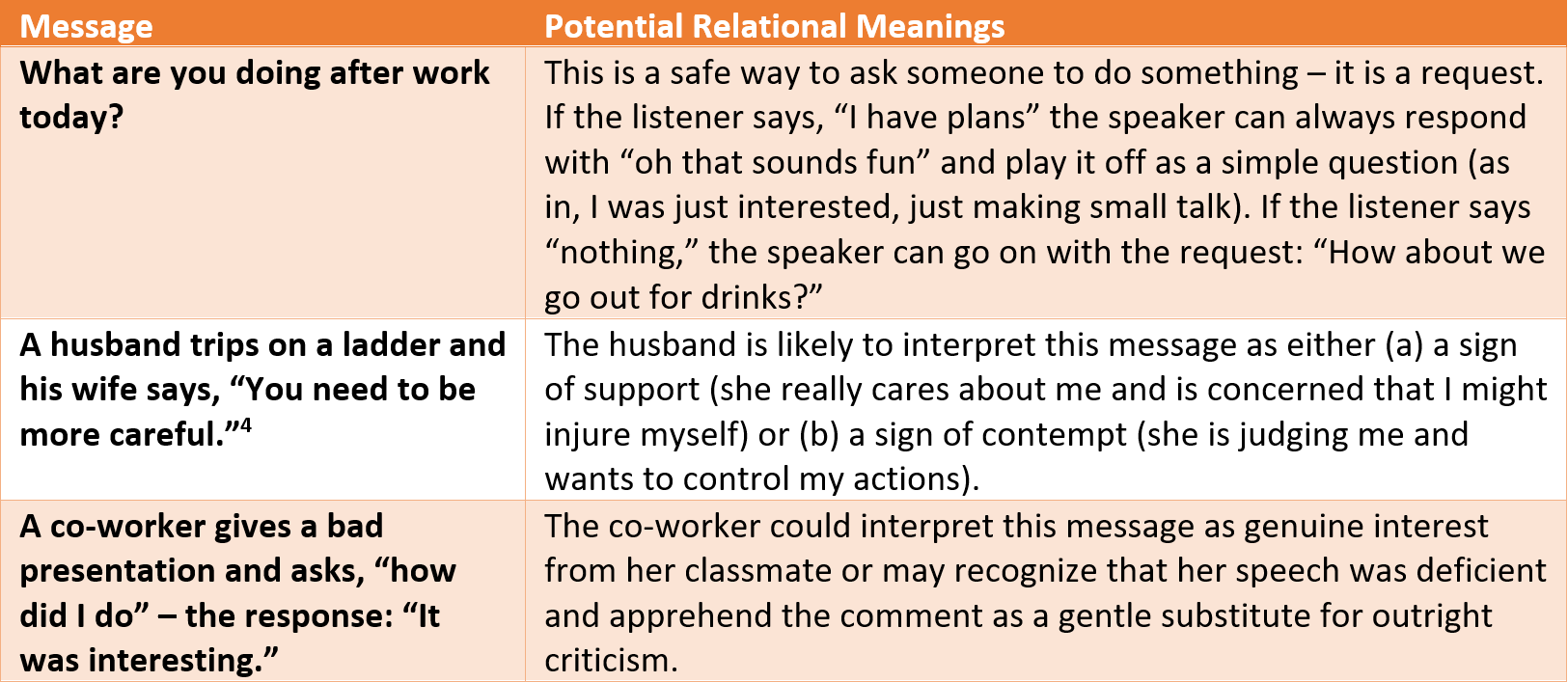

In our everyday conversations, all kinds of relational meanings get conveyed. For example, look at the following:

“Please meet me at 5:00 today.”

“We’re meeting at 5:00 today, right?”

“Don’t forget! We’re meeting today at 5:00.”

Each message has the same content - a meeting has been planned for 5:00 today. We can determine this level of meaning simply by looking at the words in each sentence. If we add up the dictionary meaning of the words, we get the content meaning of the sentences. In our examples, each says (content-wise), “two people are meeting at 5:00 today.”

But, each sentence does not mean the same thing, at least not if we consider relational meaning. The first is polite and connotes an equal relationship, one in which both people have similar levels of power and respect for each other. The second and third signal different types of relationships. The second message seems to say, “You have information that I need, please give it to me.” The third message, however, connotes a power differential whereby the sender is almost chastising the recipient – perhaps this is a relationship in which the recipient is generally forgetful or unreliable. At the relational level, the third message says, “Because you are so unreliable, I am now reminding you that we are meeting at 5:00.”

I have included a few additional examples below to reiterate the point.

Sensing involves taking in all of the available information. To be a professional listener, you must be able to not only sense the actual words but also pick up subtle verbal and nonverbal cues that signal how the speaker is thinking and feeling about the relationship being established. To assess sensing, you have to ask yourself – what does the speaker mean by saying these words (or engaging in these behaviors) in these ways?

Processing

Once the other person’s actions, intentions, and goals have been sensed, they have to be processed. Processing is something that happens internally, inside the mind of the listener. Processing involves synthesizing conversational information and remembering details as well as constructing a viable interpretation of what has been said.[4]

Scholars usually talk about the processing functions of listening as several stages that we go through when we receive a message. An example model is provided as Figure 2.

Figure 2. A Constructivist Model of the Processing Components of Listening, used with permission[5]

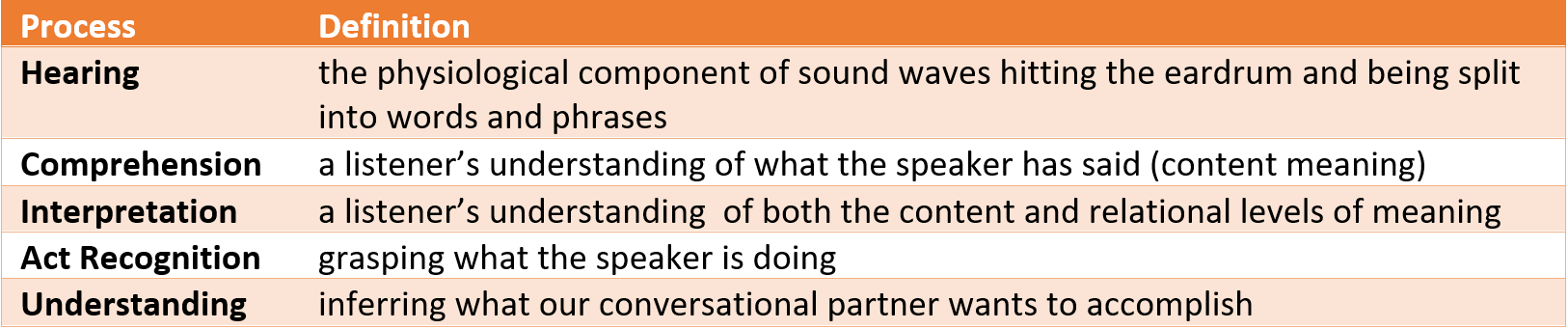

The Oxford English Dictionary defines the first stage, hearing, as “To perceive, or have the sensation of, sound.” Hearing refers to the physiological component of sound waves hitting the eardrum and being split into words and phrases.[6] Sounds are not only “heard” but also comprehended to greater or lesser extents. Comprehension, the second stage, refers to a listener’s understanding of what the speaker has said (content meaning). Comprehension is complete when the listener knows what was said or expressed without necessarily knowing what the speaker means.

To understand what a speaker means, the listener goes through the third stage, the act of interpretation or making “sense of messages by choosing from the available meanings.”[7] When we grasp the meaning of a person’s message, we understand both the content and relational level of meaning (see above). Once we can interpret these two levels of meaning, we can move to the fourth stage, act recognition, or grasping what the speaker is doing. When we communicate, we perform actions –we comfort, persuade, direct, inform, request, promise, and so forth. As a listener, you have to recognize the act a speaker if performing.

The final stage, understanding, refers to inferring what our conversational partner wants to accomplish. For instance, when a friend asks, “So, what are you doing on Saturday?” we are likely to understand that our friend is asking whether we have plans that might disallow in helping him move. If you recall from above, asking “What are you doing after work today?” is a safe way to ask someone to do something. Depending on the answer to that initial question, the speaker can adjust. It also gives the listener a non-threatening way to decline an invitation without having to actually decline. If “I have to meet my brother for dinner” after work, I cannot possibly have drinks.

As a summary of our state model of processing:

To illustrate these stages in action, suppose your boss says the following:

“Hey, can you take a walk with me?”

Assuming these soundwaves register your eardrums, you can hear the message. You also are likely able to grasp the words that your boss is using—you know the conventional use of the term walk, and you know what walking means. So, you comprehend. You also know the relationship implied by your boss asking this question—that your boss is in a hierarchically more powerful position than you and can ask you this question because of that position. So, you can accurately interpret. You also understand your boss’s intention—by speaking these words, your boss is, in effect, inviting you to accompany her to have a private conversation; she is not literally asking you about your ability to put one foot in front of the other. You now have act recognition. And you probably have an adequate understanding of your boss’s motives. For example, you know that your boss likes to discuss delicate matters in private. To round off the stages, you have understanding.

So, while the question is actually a yes-no question; that is, the content of the question is literally asking about your physical ability to walk—your knowledge of your boss, the workplace, and how the phrase is typically used help you know to say, “Sure,” then stand up and start moving.

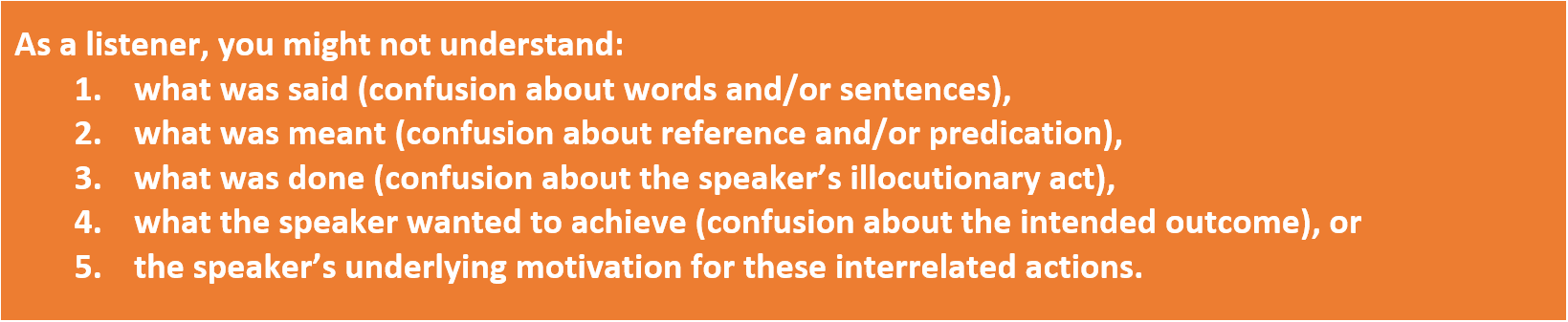

All speaker actions – from the words used to the nonverbal behaviors that accompany the words – must be interpreted by the listener. Importantly, each stage in the process represents a potential source of misunderstanding.

As we listen, the chances of us making a mistake are pretty good. It is up to us to do two important things as listeners:

We must analyze our listening to ensure we are not engaging in activities that will inhibit our hearing, comprehension, interpretation, act recognition, or understanding. Research suggests there are several meta-cognitive listening strategies you can use to monitor your listening. Meta-cognitive listening strategies are basically things you do prior to listening, while you are listening, and after you engage as a listener that help you improve.[8] There is real power in thinking before you listen!

We must be aware of how we are behaving as a listener – that is, how we are responding (the final element of listening). More information about responding continues below.

Responding

Responding is behavioral; it is the outward sign that something is occurring inside the listener. Speakers only know that listeners are adequately sensing and processing if they respond appropriately - by using the speaker’s language, asking for clarification when appropriate, and paraphrasing different parts of the speaker’s talk, for example. Listeners also engage in eye contact, head nodding, and a range of other nonverbal actions to signal attention and understanding.

Without appropriate responding, the speaker has no clue whether the listener is actually paying attention or is only pseudo-listening. When you respond, you indicate to the speaker what you have sensed and how you have processed that information.

Responding includes a range of verbal and nonverbal behaviors from eye contact to asking questions for clarification. The key to remember about responding is to indicate attention.

Now, I am not a big believer in universals – things that are true for all people at all times in all situations. There are, however, a few universal truths when it comes to responding.

In order to respond appropriately, you must be present – not on your cell phone, not thinking about other things, not distracted by what you have to do later. You have to be there, and not just physically but mentally as well. If you do not have the time to focus attention on the other person, then you have to be honest. Tell them that you are quite interested in what they have to say, but that you need some time to finish up what you are doing so that you can fully attend to them and their issues.

Assuming you are present, when you listen the surest way to indicate that you are not interested is to interrupt. Although you may not be aware of it, you have a tendency to interrupt. We all do! It’s natural to want to share your opinions and give your two cents. For most listening situations, your opinion does not matter. The speaker is not always talking to you to hear your side of the story. The speaker often wants to tell his or her side of the story and for you to listen to it without interruption.

To resist the temptation to interrupt, try focusing on what the other person is saying, then paraphrase or ask questions to get them talking more. How do you do this? I have developed a short video that you can watch below to gain some initial insights.

Good listening starts with abilities to sense and process information – how can you respond appropriately if you do not first take in all the needed information and process it sufficiently? But responding is what others see and is therefore imperative to get right. Ultimately, it is the other individual in the conversation – the customer, client, fellow co-worker, friend, family member, spouse, child, cashier, pastor, whomever – who gets to decide whether you are “competent” or “incompetent.” Perception of listening ability is the reality of your listening ability.

When you look uninterested, you are not interested. When you look inattentive, you are not paying attention. When you look bored, you are bored. It does not matter how much you are interested, paying attention, or enthralled in the conversational topic – if you do not look like you are listening, you might as well not be paying attention at all.

The importance of responding cannot be understated, and that is why we are excited to provide you with additional resources – ways of engaging as an active listener that will not only show you care but also will help you get more out of others’ speech.

Conclusion

We live in a culture that stresses the power of speech. We are told to “think before you speak” and “speak your mind” – but where are the reciprocal statements for listening? We are not instructed to think before we listen or to believe that we should fully listen to others. At the same time, truly attending to others can be the most powerful way to connect. Whether it is your friend, family member, co-worker, client, or student; everyone has a need to be understood. Listening effectively can allow you to fulfill that need.

Your ability to become a professional listener starts with knowing what listening is and what it can help accomplish. Now that you understand that listening includes abilities to sense, process, and respond, you can start to learn skills within each of these areas that can help you improve. And with improvement in listening comes better relationships, more productive work environments, and a general betterment of the human condition. And that is what the Listen First Project is all about.

My friends & colleagues could use Listen First!

Great! As the backbone of the bridging divides movement, Listen First Project works hard to lift up and make accessible resources, programs, and trainings offered by our Coalition partners across the nation who are working to bridge divides through skills of Listening, Dialogue and Collaboration. Check out Conversation.Us to learn more about the resources available to you. If you’d like to take your skills to the next level and earn a digitial badge and/or microcredential for you skills as a bridge building, check out our Bridging Movement Badging and Microcredential Program.

Graham D. Bodie, Ph.D.

Chief Listening Officer

School of Journalism and New Media

The University of Mississippi

grahambodie.com

References

[1] Bodie, G. D. (2011). The Active-Empathic Listening Scale (AELS): Conceptualization and evidence of validity within the interpersonal domain. Communication Quarterly, 59, 277-295. doi:10.1080/01463373.2011.583495

[2] Watzlawick, P., Beavin, J., & Jackson, D. (1967). Pragmatics of human communication. New York: Norton.

[3] Edwards, R. (2011). Listening and message interpretation. International Journal of Listening, 25, 47-65. doi:10.1080/10904018.2011.536471. Page 52

[4] Imhof, M. (2010). The cognitive psychology of listening. In A. D. Wolvin (Ed.), Listening and human communication in the 21st century (pp. 97-126). Boston: Blackwell.

[5] Burleson, B. R. (2011). A constructivist approach to listening. International Journal of Listening, 25, 27-46. doi:10.1080/10904018.2011.536470

[6] Bodie, G. D., & Wolvin, A. D. (in press). The psychobiology of listening: Why listening is more than meets the ear. In L. S. Aloia, A. Denes, & J. Crowley (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the Physiology of Interpersonal Communication. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

[7] Edwards, 2011, page 42

[8] Vandergrift, L., Goh, C.C.M., Mareschal, C., & Tafaghodtari, M.H. (2006). The metacognitive awareness listening questionnaire (MALQ): Development and validation. Language Learning, 56, 431-462. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9922.2006.00373.x

![Figure 2. A Constructivist Model of the Processing Components of Listening, used with permission[5]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55fc1c78e4b0c8c3859e4d2a/1520744546889-3FLUCRKJQB2AAPZ3NIWH/Processing+Model.png)